Ask a Theologian: Confirmation

Dear Theologian,

Can you help me understand what our sacrament of Confirmation is really all about? When I was a Roman Catholic, I was taught that Confirmation confers the Holy Spirit upon a person. But now, in the Anglican communion, I’m told that it is the rite by which a person, originally baptized as an infant, publicly renews and re-affirms the Baptismal Covenant in a personally responsible way. Which explanation is (more) correct?

Somewhat Confused

Dear Confused,

Let me approach this question by putting it into a larger theological context. There are much deeper mysteries involved in this discussion than the history or theory of ritual.

Most basic of all is the Mystery of God, as known in Jesus of Nazareth (together with all that led up to him and all that has followed from him). In our cultural world, this Mystery must never be trivialized by taking it for granted while we argue about ritual and Church arrangements.

Rather, the question of God is the burning issue for all human beings today who seek meaning and purpose for their existence. How, many ask, is it still possible to believe in God, or to speak of God plausibly?

The question about God can never be answered theoretically in a satisfying way. Only people who bear witness to the divine Goodness by their values and behavior can make belief in God plausible to others.

The Church of Jesus is called to do this, to speak of God by its very existence, and to allow the reality of Jesus to continue to reverberate in history. As he was the supreme witness to the divine Goodness, even and especially in his helplessness and suffering, so also those who bear his name are to continue the witness.

Church, therefore, must be seen as implicated in the ultimate Mystery of God and the manifestation of that Mystery in Jesus the Christ. The Church can and must be understood as “the Body” (in Paul’s sense), the corporate mystery of human beings who are being gathered, transformed, and re-created by the Holy Spirit, to be—as a community— the visible sign of Christ’s presence to the world.

If Church is understood in this dimension, and not merely in its institutional and organizational features, then one can appreciate why initiation into it could be of enormous human significance. And only then can the discussion of Confirmation be appreciated properly as the effort to understand how each member is to enter more deeply and authentically into the fellowship of the Crucified and Risen One.

Christian Initiation is the process by which an individual is brought into the corporate mystery of the Church. It is important to distinguish at least two aspects of this: (1) the actual process of instruction and formation by which a person gradually takes on the vision, values, and behavior of the Christian “Way” (2) the sacramental ritual of Initiation whereby the entry of a person into full communion with the Body is symbolized, enacted, and celebrated.

In the early Church, Initiation was celebrated sacramentally in one unified rite (water Baptism, followed immediately by laying on of hands, with or without anointing, and admission to the Table of the Eucharist). The symbolic force of the laying on of hands (sometimes with anointing) immediately after Baptism was to impart the “seal of the Spirit.”

A distinct rite, believed to impart the Holy Spirit at some time later than Baptism, came into being gradually, as a kind of accidental development in the Western Church. This happened because of the insistence that only the Bishop could perform that part of the original unified baptismal rite. This led to postponement of the concluding ceremony of Baptism for ever-increasing periods of time—ultimately, for years.

Consequently, what had originally been an intrinsic moment in the entire baptismal liturgy now came to be felt as a separate and distinct rite. Because the ritual of laying on of hands, often with anointing, had originally symbolized the gift of the Holy Spirit within the unified initiation liturgy, theologians tended to attribute to the separated ritual the efficacy of conferring the Holy Spirit.

Hence the medieval “sacrament” of Confirmation was believed to impart the Holy Spirit in a new way, beyond the efficacy of Baptism, conferring upon a person at the threshold of adulthood special gifts and “strength for the battle” (robur ad pugnam) of Christian life. This continues to be the Roman Catholic understanding of the sacrament of Confirmation.

The distinctive Anglican conception and practice of Confirmation came into being in the 16th century, influenced by the continental Reformers.

A close examination of the rite of Confirmation in the Prayer Books of 1549, 1552 and 1662 shows the attempt to combine a new function of Confirmation (the reaffirmation of baptismal vows at a mature age by a person baptized as an infant) with the old liturgical form of the medieval sacrament of Confirmation (which signified the imparting of the Holy Spirit).

Thus, two quite different and unrelated functions of “Confirmation” were combined uneasily in one ritual. This is the ambivalent heritage with which Anglican theologians, liturgists, and pastors have had to wrestle in modern times.

From our present vantage point, the effort of medieval theologians to attribute to Confirmation a new gift of the Spirit (beyond the bestowal of the Spirit in Baptism) seems to be simply a misunderstanding.

On the other hand, the ritual of laying on of hands with anointing really does have baptismal meaning (as it did originally, when it was not yet removed from its full liturgical context). That is, it is an extension of one very important meaning of Baptism: the gift of the Holy Spirit.

Not all the meanings of Baptism are symbolized by the Confirmation ritual, of course. But the meaning of being given the Holy Spirit is clearly expressed, and offers the possibility of saying Yes in freedom to this gift once given, of receiving it actively in a stance of faith which really affirms the entire commitment of a Christian.

Rightly understood, therefore, the apparent anomaly of Confirmation (as an accidentally detached symbolic fragment of the baptismal liturgy) can serve to confront a mature person with the reality of his/her Baptism.

This “extension” of Baptism into a time when the baptized is capable of an act of faith really allows him/her to relate with deliberate choice to a sacrament celebrated originally without his/her personal participation.

Faithfully,

The Theologian

The Rev. Wayne L. Fehr writes a monthly column for the diocesan newsletter called "Ask a Theologian," answering questions from ordinary Christians trying to make sense of their faith. You can find and purchase his book "Tracing the Contours of Faith: Christian Theology for Questioners" here.

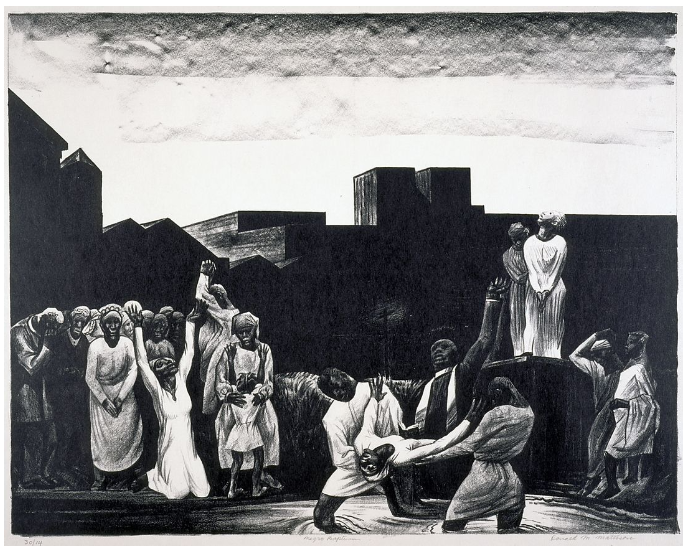

Negro Baptism by Donald Mattison (American, 1905-1975). Courtesy of the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields.

Negro Baptism by Donald Mattison (American, 1905-1975). Courtesy of the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Pentecost from the workshop of Bernard van Orley

Pentecost from the workshop of Bernard van Orley